From August 2010 until January 2013 I lived as a novice Buddhist renunciate, with a shaved head, white robes, and a Buddhist Pali name (Nyaniko). I’ve written earlier about my decision to ordain as an Anagarika, the first stage of becoming a monk, as well as about some of the gifts and insights of that period of my life.

Since then, many have asked about my choice to return to lay life. It took months of contemplation and deep listening for me to arrive at that point of clarity, and over two years to finally put these reflections into words. In considering why it’s taken so long to write, I’ve come to understand that there was something so personal about the process that I needed to let things settle inside before sharing publicly.

I took my time with the decision to disrobe, letting myself stay with the uncertainty and not knowing, working through layers of inquiry, confusion and grief, until things felt clear enough inside to act. I wanted to be sure because, as one lay teacher of mine quipped, “It’s a lot harder to get into robes than it is to get out of them.”

Leaving Home

There are times in our lives where we need to step back from everything and reevaluate. The currents of society are strong, and without time for reflection and contemplation we can find ourselves simply carried along, doing what we “should” without ever asking what we really want, what’s true for ourselves at the deepest level.

Meditation retreats provide one context for this kind of stepping back. Spending time at a monastery provides another. Initially I ordained for just one year. I had some health issues so knew I couldn’t continue on as a monk. The intention was to carve out some time with nothing planned: to settle down with no duties to the outside world and see what was what.

In the Thai Forest tradition in which I ordained, an Anagarika is a temporary role of service and training in preparation for novice ordination. It’s a liminal space: one is neither a lay person nor fully a monastic. I can recall sitting in between the laity and monks at one monastery, the seating arrangement somehow representing my place at the edge between two worlds.

As my taste for monastic life grew, I began to consider staying in white more long-term, as a life path. Yet choosing to live as an Anagarika would mean moving through the world in this perpetual liminal state – belonging to neither lay society nor to the monastic world.

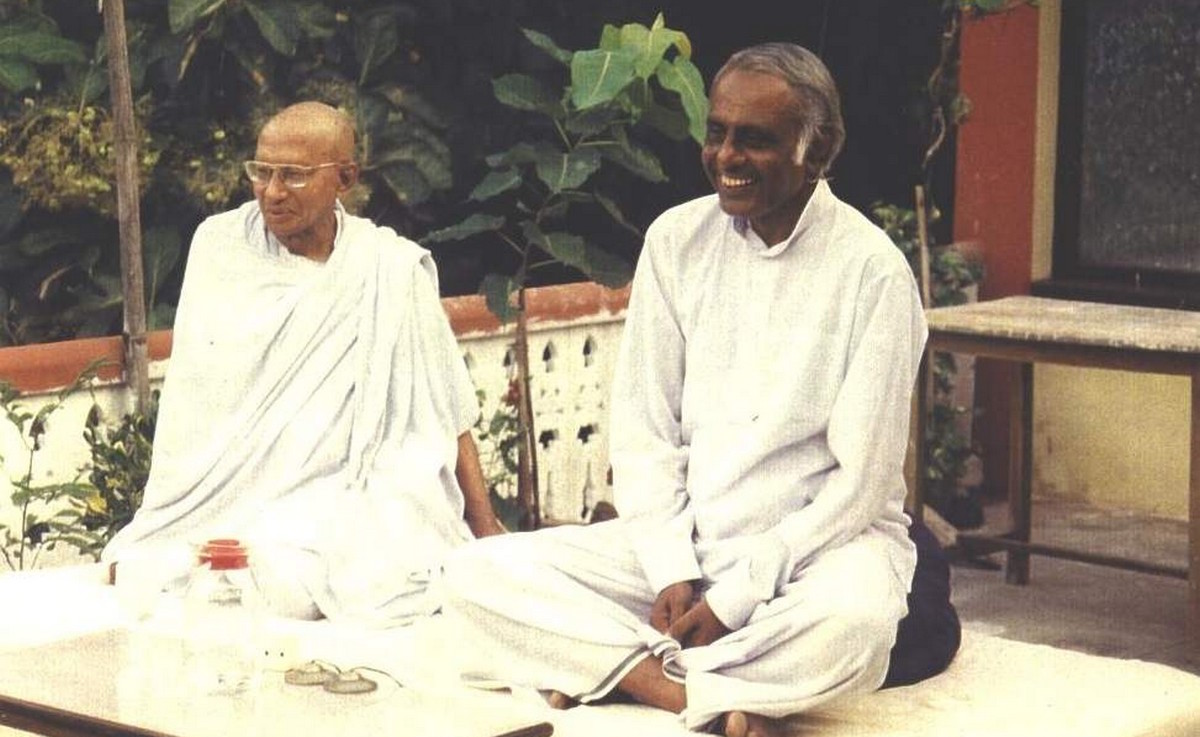

In modern times, there have been two well known Buddhists who lived as Anagarikas: Anagarika Dharmapala (1864-1933), and Anagarika Munindra (1914-2003). Munindra-ji was one of my first teachers. My other first teacher, Godwin Samararathne, also wore white. I felt inspired by the possibility of following in their footsteps and living the life of a lay renunciate.

Anagarika Mundindra-ji and Godwin Samararathne, Bodh Gaya India

Yet they had lived in Asia (in India and Sri Lanka respectively), where there is a long-standing history of renunciation, and where wearing white has been a common religious practice for millennia.* Here in the West, there is no cultural context for this. This doesn’t preclude doing it – it just means it’s a lot harder to pull off.

Taking Off the Mask

The word Anagarika literally means “homeless one” – one who has left the household life. In the early texts, the Buddha uses the term to refer generally to all of his monks and nuns. In an important sense, the physical homelessness represents a kind of psychological homelessness.

The renunciate relinquishes the need for a fixed role and identity in service of finding a more reliable and enduring refuge: the true home of the human spirit. This is the home of awakening, of the heart resting in its own nature, liberated from grasping, fear and delusion.

In shedding the roles of society, I felt the freedom to discover from the inside who I was and what I genuinely wanted. At the monastery, it was as if I had taken off a mask called “Oren.” Oren the son; Oren the brother; the friend, musician, lover, nonprofit director… As I shed family, professional, and relational roles, the masks of psychological identity became apparent: the handsome one, the intelligent one, the funny one, the perfect one who has it all together…

The structure and simplicity of monastic life is designed to strip everything away. The gift of stepping out and taking off the mask is that, if we pay close enough attention, we get some insight into the relative nature of our identities, and glimpse something deeper about who we really are.

What does it mean to really leave home? To give up our reliance on the safety of our role or identity? Monastic life is a training, a time-tested structure for spiritual development. But the Buddha was clear that what makes one a true seeker is not one’s birth, one’s clothes, or the rituals one performs. It is what’s in one’s heart, one’s words, and one’s deeds.

Becoming Myself

After two years in white, questions began to arise. Though I hadn’t ordained to run away from the world or hide out (a common stereotype of monastics), I found that over time I had begun to wear a new mask! Because the slate doesn’t just stay clean by itself. The process of forming an identity is so deeply engrained that the heart-mind forms around anything it can. This time it was Nyaniko, Buddhist Anagarika, lay renunciate; the quiet one, the composed one, the special, devoted one…

Anagarika training took effort and had true integrity, but it also meant there were certain aspects of myself and my life that I could avoid. For example, there were ways in which I didn’t encounter social anxiety or the need for peer belonging, as monastic life encourages an aloofness in service of contemplation. The monastic form’s value for solitude protected me against fully feeling my loneliness. I also didn’t need to face wounds around sexuality or my identity as a sensitive man with “feminine” qualities in a patriarchal culture with strong gender roles.

None of this is inherent in the form. It is entirely possible to meet and heal such places within the confines of the robes, and I know many monastics whose drive for inner freedom has allowed them to do just that. The question, however, was what would serve me best? What was the most conducive form for healing and awakening?

A Question of Character

The exploration took me further inward, to a recognition and deep acknowledgment of what I will call my character. Peace isn’t found by rejecting or denying our individual, unique make-up. It comes through understanding the conditioned, impersonal nature of our identity and fully inhabiting it with more freedom. As it’s said, one becomes more and more oneself on this path.

By stepping out of my worldly roles and identities, I was able to examine and reinhabit them in a different way. I began to fully accept my relational nature that values belonging and community, and that thrives on strong social connection. I embraced my artistic, creative side (though I’ve yet to pick up the guitar again). I acknowledged my need for touch, my desire for companionship, and my interest in growing emotionally through intimate relationship. And, most of all, I owned my deep longing for a sense of place in the world, for contributing in a meaningful way.

These parts of myself were attenuated by the monastic life, which is structured around norms and standards aimed at simplicity and letting go rather than authentic self-expression. The longer I stayed in white, the more I noticed certain fundamental misalignments. I loved the simplicity, the devotion, and the support for study and practice. Other parts weren’t a fit.

Tisarana Buddhist Monastery, Fall 2013

Serving and Teaching

Since the time I was first introduced to meditation I wanted nothing else but to understand the practice well enough to be able to share it with others. I dreamed of following in the footsteps of my first teachers. Yet when I looked clearly I realized that I had been holding on to an ideal image of what I wanted to represent for others, rather than asking honesty what I needed.

Teaching as an Anagarika was complicated. As a junior trainee, I couldn’t teach in the monasteries. Yet in the lay community, the shaved head and white robes created a distinct barrier.

While the renunciate holds important inspirational value for the lay community, I was more interested in integrating the practice into contemporary life. I wished to teach in the vernacular, in a role and language that people could relate to. If I were to be a truly effective teacher, I needed to continue my training “in the trenches,” handling the stress and pressures of modern life.

Loss and Letting Go

The more I accepted these larger disconnects, the more I saw other ways the form wasn't working for me. My health challenges made it difficult to follow the monastic schedule and meal restrictions. Medical bills required money. The perpetually subordinate role in the hierarchy did not serve my personal growth as an adult. And strong ties with family and friends tugged at my heart.

I loved living as a renunciate. The way of life, its ideals, and community are tremendous supports for waking up and training the heart-mind. Yet as I recognized the host of conditions that were not aligned, the range of my needs that weren’t being met, loss was the final piece I needed to face.

I was afraid that my monastic teacher would be disappointed in me, that I would lose his respect or the closeness we shared. But in conversation he was always supportive and open-minded, encouraging me to find my own way. I was also afraid my community or peers would judge me, but they consistently expressed unconditional support.

I realized that I was afraid of disappointing myself, and that I feared self-judgment at ‘failing’ or ‘giving up.’ I also noticed that I didn’t want to let go of being different or special – that disrobing meant having to face being ordinary, just like others, and wanting to belong.

And I understood that at the root level, I simply didn’t want to feel the grief and sadness of ending this unique and sacred experience. When I finally allowed these feelings to enter my heart and move through me, the process came to completion. I was able to honor what I had been sensing. The choice to return to lay life was clear.

A Life of Meaning

One of the most central questions for humans is meaning. To thrive, we need a sense of purpose and direction. We long to feel connected with something larger than the mundane concerns of our day to day lives.

Both my choice to ordain and my choice to return to lay life were driven by that yearning for inner fulfillment. My calling in life has been clear for many years: to cultivate a loving and peaceful heart, to mature in wisdom, and share with others the gifts and blessings of spiritual practice.

The fruits of training as a Buddhist renunciate stay with me. Though I’ve let go of the outward form, I do my best to carry forward the qualities that I touched, the perspectives and practices I studied. Lay life is a very different form, with different challenges and learnings. I feel content in knowing that I’ve chosen consciously.

* The practice of wearing white on lunar observance days goes back to ancient India and likely predates the Buddha. This practice continues in Buddhist Asian countries today. Also many Asian women, unable to ordain as nuns due to the patriarchal politics of institutional Buddhism, wear white and follow renunciate precepts.